What is Basic Life Support?

By Anoushka

Disclaimer: The following text is for informational purposes only and should not be attempted unless by someone who holds a valid First Aid Training certificate. The information was correct at the time of writing, but BLS is constantly being updated.

Basic life support (BLS) is arguably one of the least basic skills on the medical school curriculum – though it’s one of the most important. BLS is also taught outside of medicine to teachers, lifeguards, sports coaches, and all first aiders.

BLS comprises a collection of actions performed to keep someone alive when their fundamental survival mechanisms (open airway, adequate breathing, effective heartbeat) have stopped working.

The BLS actions I have been taught are found below, grouped according to which fundamental survival mechanism they aim to rectify.

Fundamental survival mechanism #1: airway

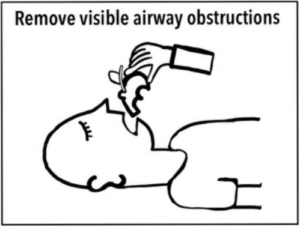

Removing debris. If you can see an object obstructing their airway, remove it.

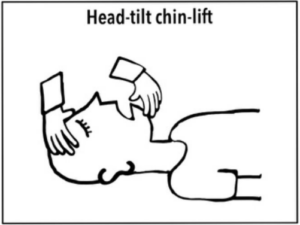

Head-tilt chin-lift. If their airway isn’t properly open and there is no possibility of broken bones in their neck (called a c-spine injury), tilt their head backwards and lift their chin upwards, putting one hand under their chin and the other on their forehead.

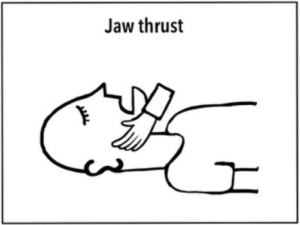

Jaw thrust. If their airway isn’t properly open but they might have a c-spine injury, don’t tilt their head backwards. Instead, place your hands behind their jawbone on either side and bring their jaw forwards.

Fundamental survival mechanism #2: breathing

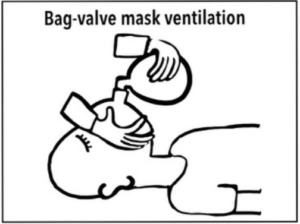

Bag-valve mask rescue breaths. If the patient is not breathing and there is a bag-valve mask available to use (e.g. in. a first aid kit) that’s lucky! Place the mask over their nose and mouth and squeeze the bag to push air into their lungs.

Fundamental survival mechanism #3: circulation

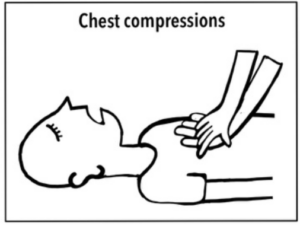

Chest compressions. Place the palms of your hands (with one hand on top of the other) in the centre of their chest, just below their ribcage. Push down firmly every second. Chest compressions aim to push blood around their body while their hearts aren’t doing it properly.

For a person carrying out chest compressions, seconds can be timed using a phone or clock, or by singing a song – such as ‘staying alive’ by the Bee Gees, which has one beat per second. Chest compressions are pretty tiring – so its useful to let another person take over if possible.

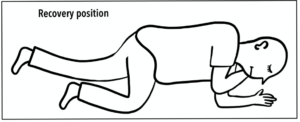

Maintaining survival after initial BLS: recovery position

If an unconscious casualty has an open airway, adequate breathing, and an effective heartbeat, shift them so that they are lying on their side with their legs slightly bent, resting their cheek on their elbow, with one arm resting in front of their abdomen. This will decrease the risk of their tongue obstructing their airway, or their limbs getting injured.

It is the job of a BLS practitioner to work out what is wrong with the casualty, quickly call for help, and perform an appropriate sequence of BLS actions. Some important BLS sequences are found below.

- Assessing a casualty to determine which BLS they need:

- Check the area is sufficiently safe for you to approach.

- Check if the casualty is conscious by giving their shoulders a gentle shake and asking them if they can hear you.

- Check for airway and breathing by looking for airway obstructions, listening for breathing sounds, and feeling whether their chest rises and falls. Lie the casualty on their back for this.

- Check for circulation by feeling for a pulse in their neck (for adults and children) or groin (for infants under 1 year).

If 2,3 and 4 demonstrate an unconscious patient, inadequate breathing or an absent pulse, call for help immediately. Out of hospital, this might involve asking a nearby person to call an ambulance and come to assist you with BLS. Inside hospital, internal telephone systems and emergency buttons alert specialist teams to come to the patient as soon as possible.

- Adult CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) – use for an adult who has an open airway but inadequate breathing and circulation:

- 30 chest compressions (one compression per second)

- 2 rescue breaths

- Repeat 1 then 2 until help arrives, or until the or until the adult begins independently breathing and maintaining their heartbeat, in which case put them in recovery position. If the adult is pregnant, lie them on their left hand side so that their uterus does not squash their veins to make their circulation worse.

- Paediatric CPR – use for a child (1-18 years) with an open airway but inadequate breathing and circulation:

- 5 rescue breaths

- 15 chest compressions (one compression per second)

- 2 rescue breaths

- Repeat 2 and 3 until help arrives, or until the child begins independently breathing and maintaining their heartbeat, in which case put them in recovery position.

Conclusion

BLS is lifesaving if performed correctly. More up to date information and guidelines for BLS can be found on the UK-resuscitation council website (https://www.resus.org.uk).